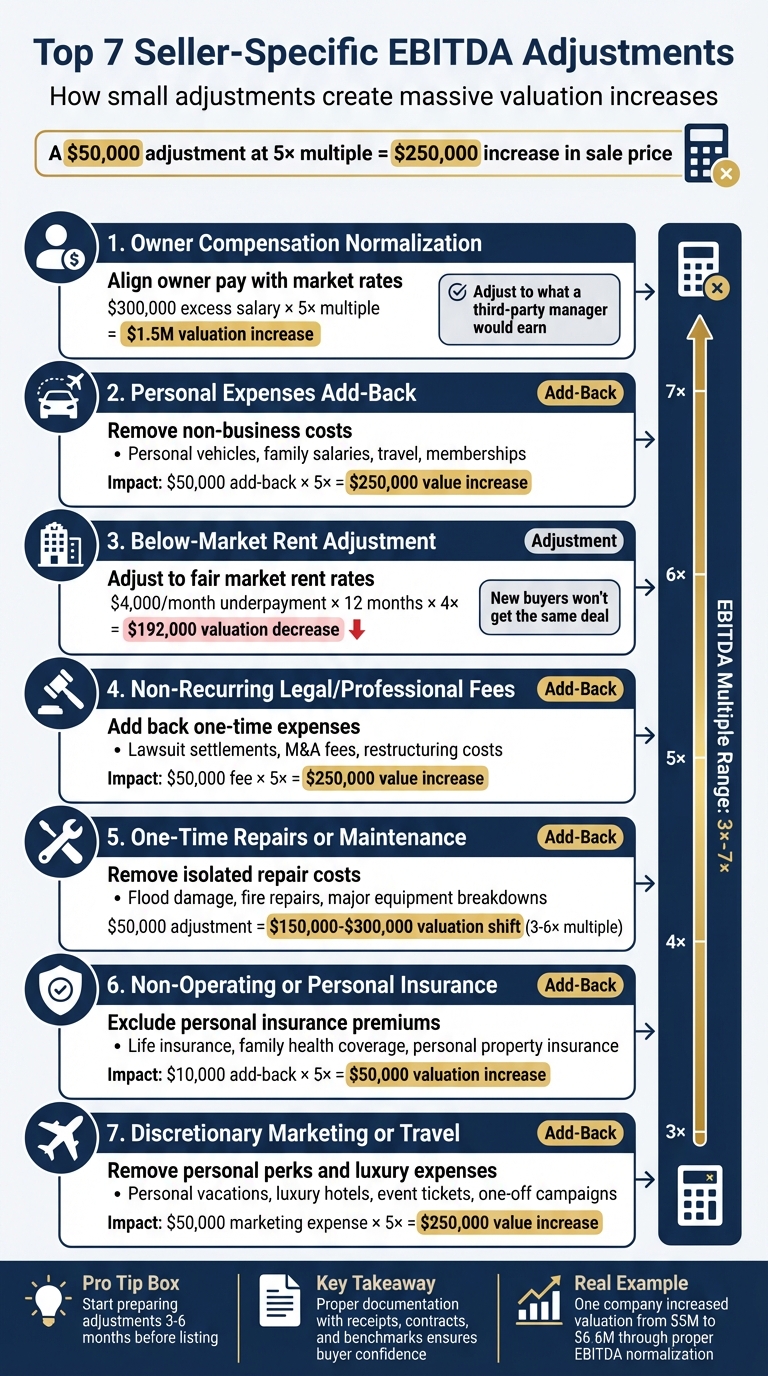

When selling a business, adjusting EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) is crucial to reflect the company’s actual profitability under new ownership. These adjustments can significantly impact the business’s valuation, as buyers often apply multiples (3x–7x) to the adjusted EBITDA. For example, a $50,000 adjustment could increase the sale price by $150,000–$350,000.

Here’s a quick rundown of the 7 key EBITDA adjustments you need to know:

- Owner Compensation Normalization: Align owner pay with market rates. Overpaid or underpaid owner salaries are adjusted to reflect what a third-party manager would earn.

- Personal Expenses Add-Back: Non-business-related expenses (e.g., personal travel, family wages, or private memberships) are added back to EBITDA.

- Below-Market Rent Adjustment: If the business pays below-market rent, adjust EBITDA to reflect fair market rates.

- Non-Recurring Legal/Professional Fees: One-time expenses like lawsuit settlements or consulting fees are added back to EBITDA.

- One-Time Repairs or Maintenance: Isolated repair costs (e.g., flood damages) that don’t reflect normal operations are adjusted.

- Non-Operating/Personal Insurance: Personal insurance costs (e.g., health or life insurance for family members) are removed from operating expenses.

- Discretionary Marketing or Travel: Personal trips, luxury upgrades, or non-essential marketing expenses are added back.

Why it matters: Properly documenting these adjustments with receipts, contracts, or benchmarks ensures buyer confidence and avoids valuation discounts during due diligence.

Pro Tip: Start preparing these adjustments 3–6 months before listing your business for sale to maximize its value.

7 Key EBITDA Adjustments That Increase Business Valuation

10 Adjustments to EBITDA

1. Owner Compensation Normalization

Adjusting owner compensation is one of the most common EBITDA adjustments in business valuation. Many private business owners structure their pay to minimize taxes rather than align with market rates, leading to distortions that need correction before determining the company’s value.

The idea is straightforward: align the owner’s compensation with an "arms-length" market rate – essentially, what a third-party manager with no ownership stake would earn for doing the same job. For example, if an owner is paid $500,000 but the market rate for the role is $200,000, the $300,000 difference can be added back to EBITDA. At a 5× multiple, this adjustment could increase the business’s value by $1.5 million.

On the flip side, if an owner earns $100,000 when the market rate is $200,000, you would reduce EBITDA by $100,000. At a 5× multiple, this would decrease the valuation by $500,000.

It’s important to note that you should only adjust the portion of the salary that exceeds – or falls short of – the market rate. Erik Sullivan from MidStreet emphasizes this point:

Adding back the full $200,000 rather than the fair-market salary inflates the valuation… companies valued using EBITDA won’t be owner-operated, so a fair-market-value salary (to be paid to a hired manager) is more appropriate.

These adjustments should also account for related expenses like payroll taxes (approximately 8%), health insurance (around 5%), and retirement contributions. For instance, a $300,000 add-back might also require adjustments for $24,000 in payroll taxes and $15,000 in health insurance costs.

To ensure accuracy, document your market-rate assumptions using industry salary surveys or reliable benchmark data. Buyers will meticulously review these adjustments during due diligence. Once compensation is normalized, it sets the foundation for evaluating other seller-specific adjustments, such as personal expense add-backs.

2. Personal Expenses Add-Back

It’s not uncommon for business owners to charge personal expenses to their company accounts as a way to reduce taxes. However, these non-operational costs – like vehicle payments or country club memberships – need to be added back to EBITDA. This step ensures an accurate financial picture, but it requires thorough documentation to maintain credibility.

The key question to ask is: Would a third-party owner incur this expense? If the answer is no, the expense should be added back since it skews EBITDA. Some typical examples include:

- Personal automotive costs (e.g., monthly payments, fuel, insurance, or repairs unrelated to business use)

- Salaries paid to family members who don’t actively work in the business

- Expenses for personal travel or vacations

- Meals without clients or employees

- Personal insurance premiums

These adjustments can have a huge impact. For instance, a $50,000 add-back could increase the purchase price by $250,000 if a 5× EBITDA multiple is applied. In one real-world example, normalizing EBITDA from $1,000,000 to $1,320,500 raised a company’s valuation from $5 million to over $6.6 million.

To identify such adjustments, review the General Ledger line by line, looking for transactions that benefit the owner personally. However, avoid cluttering the financials with minor adjustments – ignore items below 0.5% to 1.0% of EBITDA.

As with any normalization process, proper documentation is crucial. Every add-back should be backed by solid records, such as receipts, invoices, or mileage logs, since buyers will closely examine these during due diligence. Jacob Orosz, President of Morgan & Westfield, explains:

Value is a function of risk. The lower the risk, the higher the value. A buyer who’s dealing with a conservative seller will view the transaction as less risky and may pay a higher multiple.

On the flip side, poorly documented adjustments can raise red flags for buyers, increasing skepticism and potentially lowering the valuation.

3. Below-Market Rent Adjustment

Sometimes, businesses lease property at rents below market rates. While this arrangement might work well for the current owner, it can create misleading EBITDA figures. A new buyer likely won’t enjoy the same deal and will need to pay market rates, which impacts profitability.

To address this, you’ll need to calculate the fair market rent by comparing similar commercial leases in the same area. This comparison helps identify the gap between the current rent and what the market demands. That difference is then deducted from EBITDA, giving a clearer picture of actual operating costs. For example, if a business is underpaying rent by $4,000 per month (or $48,000 annually), and the EBITDA multiple is 4×, this adjustment could lower the valuation by around $192,000.

Neal Patel from Reliant Business Valuation emphasizes the importance of this adjustment:

Appraisers must assume that a hypothetical buyer of the business will not benefit from the existing close relationship between the business and real estate.

Backing up this adjustment with evidence is essential. Use third-party benchmarks, professional appraisals, or comparable lease agreements to support your calculations. Solid documentation ensures the adjustment is credible and defensible.

4. Non-Recurring Legal and Professional Fees

One-time legal or professional fees – like lawsuit settlements, M&A advisor expenses, or restructuring consulting – aren’t part of a business’s regular operating costs. Because of this, they should be added back to EBITDA to provide a clearer picture of ongoing profitability.

Here’s an example: At a 5× EBITDA multiple, adjusting for a $50,000 one-time legal fee could increase the purchase price by $250,000.

Industry professionals emphasize the importance of this adjustment. Travis Borden, Founder of Keene Advisors, notes:

One-time and non-recurring costs are expenses that would not be incurred during the normal course of business. These expenses distort a company’s historical operating expenses and understate reported EBITDA.

It’s essential to distinguish between recurring and one-time fees to maintain credibility. Recurring costs – like annual corporate filings, routine contract reviews, and monthly bookkeeping – are part of the business’s normal operations and should remain in the EBITDA calculation. On the other hand, expenses such as lawsuit settlements, transaction-related fees, or special tax restructuring projects are non-recurring and should be added back. This distinction is crucial for accurate and trustworthy EBITDA normalization.

To ensure transparency, document all one-time fees with organized invoices, contracts, and financial records. Also, take a close look at the "Other Income and Expenses" section for any hidden items. Buyers will carefully examine these adjustments, so detailed documentation and clear communication are essential.

sbb-itb-798d089

5. One-Time Repairs or Maintenance

After addressing legal and professional fees, it’s essential to consider one-time repair or maintenance costs when normalizing EBITDA. These large, non-recurring expenses can skew a business’s actual earning potential.

Take, for instance, unexpected repairs caused by floods, fires, or major equipment breakdowns. These isolated events don’t represent the day-to-day operations of a business. To put it into perspective, a $50,000 adjustment to EBITDA can translate to a valuation shift of $150,000 to $300,000, using a typical 3–6× multiple.

Another area worth examining is how capital expenditures are categorized. It’s not uncommon for private business owners to classify significant, long-term investments – like a major production line upgrade – as "repairs" to lower their tax obligations. This tactic might reduce short-term liabilities, but it also lowers historical EBITDA and, in turn, the overall valuation of the business. Chase McClung, Partner at Windes, highlights this point:

EBITDA normalization allows you to identify items such as a one-time server upgrade or a major production line overhaul and treat them as Capital Expenditure rather than Repair Expense.

To ensure accurate adjustments, thoroughly review the "Repairs and Maintenance" account. Separate capital expenditures from routine maintenance, and back up your claims with clear documentation like invoices, receipts, or insurance claims. Buyers will closely examine these adjustments, as they directly impact the purchase price. Deferred maintenance – delaying necessary repairs to temporarily boost profits – can lead to a negative adjustment, reducing the business’s valuation. Addressing any deferred maintenance before listing the business can help avoid giving buyers a reason to lower their offer.

The rule of thumb is straightforward: if the expense is non-recurring and unrelated to normal operations, it qualifies as an add-back. For example, costs tied to maintaining non-essential assets, like a company-owned vacation property, fall into this category since they aren’t critical to the core business. By carefully distinguishing these expenses, you ensure that only recurring, operational costs are reflected in the adjusted EBITDA, helping to present a clearer picture of the business’s true profitability.

6. Non-Operating or Personal Insurance

Personal insurance expenses charged to the business are often overlooked during EBITDA normalization, but they can have a big impact on valuation. Like other seller-specific adjustments, these add-backs require thorough documentation and a market-rate analysis. These expenses usually include the owner’s personal life insurance (such as "key man" policies), as well as health, dental, and medical insurance premiums that won’t carry over to a new owner. Insurance for assets unrelated to the business – like the owner’s primary residence, vacation homes, or personal vehicles – should also be excluded.

It’s important to separate essential business insurance from perks that benefit the owner. Necessary operating expenses like general liability, workers’ compensation, and professional indemnity insurance should remain part of EBITDA calculations. On the other hand, insurance premiums covering family members who don’t actively contribute to the business are treated as full add-backs. Making this distinction ensures valuation adjustments are accurate.

Jacob Orosz, President of Morgan & Westfield, offers this advice:

Any personal insurance expenses such as health insurance, dental insurance, and life insurance, should be adjusted to what might be considered reasonable for a president of a company of your size.

Every valid insurance add-back can significantly increase the valuation. For instance, a $10,000 add-back at a 5.0× multiple adds $50,000 to the valuation. In one example, a $15,000 health insurance add-back raised the valuation from $5 million to roughly $6.6 million.

To support these adjustments during due diligence, export the general ledger to Excel and flag personal insurance entries. Obtain original insurance policies or invoices to confirm who is covered and whether the insured property is tied to business operations.

As noted by Axial:

Personal insurance policies, cell phones and related perks – acceptable as add-backs when tied solely to the owner’s benefits. Since these expenses cease post-transaction, they qualify as add-backs.

7. Discretionary Marketing or Travel

Sometimes, owners include discretionary marketing, travel, or entertainment expenses in operating costs, which can inflate the numbers. These might include personal trips labeled as business travel, stays at luxury hotels, exclusive memberships, event tickets, or even one-off marketing campaigns. In family-owned businesses, it’s not uncommon to see expenses like sponsoring local events or charities in the owner’s name added back to EBITDA. Identifying these expenses is crucial to distinguish between essential business costs and personal perks.

For example, travel that’s directly tied to business operations – like attending trade shows or meeting with clients – should remain as part of operating expenses. However, personal vacations or luxury upgrades for the owner? Those definitely qualify as add-backs. Morgan Felber, Senior Financial Analyst at Lutz, illustrates this with a clear example:

If a one-time marketing expenditure of $50,000 is added back, and the transaction EBITDA multiple is 5x, the transaction value or purchase price increases by $250,000.

This kind of clarity is essential for the normalization process we’ve discussed earlier.

To ensure transparency, keep detailed records to back up these add-backs. Save invoices, receipts, and contracts for any discretionary travel or marketing expenses. Work with your CPA to create reports that clearly separate personal travel or entertainment costs from business-critical ones. The goal? To present a realistic, defensible picture of the business’s earnings – without the influence of owner-specific perks.

Conclusion

Documenting seller-specific EBITDA adjustments isn’t just about crunching numbers – it’s about showcasing a business’s true earning potential and earning buyer confidence. Since businesses are often valued as multiples of EBITDA, even minor adjustments can have a big impact on their overall value. Take, for instance, a 2025 case involving a family-owned company that worked with Keene Advisors a year before its sale. They uncovered $6.6 million in standalone costs and one-time expenses. By cleaning up their financials and thoroughly documenting these adjustments, they sold the business to a private equity firm for over 13 times EBITDA – adding more than $86 million in value compared to the unadjusted figures. Once adjustments are locked in, timing becomes the next critical step.

Starting early is key to maximizing valuation. Aim to prepare your adjustment schedule 3–6 months before entering the market. Keep everything detailed and transparent – line-by-line explanations backed by external evidence like invoices, contracts, and payroll records make all the difference. As Travis Borden, Founder and CEO of Keene Advisors, emphasizes:

One of the most important things a founder or CEO can do to maximize value in a sale transaction is to increase earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization ("EBITDA").

Thorough documentation also helps reduce buyer skepticism and keeps deals moving smoothly through due diligence. Buyers tend to approach seller-provided figures with caution. In fact, a study of 600 M&A and LBO transactions revealed that total addbacks averaged 53% of reported last-12-months EBITDA at the start of a deal. This shows buyers expect adjustments – but they also expect those adjustments to be defensible and backed by solid evidence.

For business brokers and M&A advisors, presenting these adjustments clearly is non-negotiable. Tools like Deal Memo can help by delivering on-demand CIM/OM packages in just 72 hours, bridging the gap between reported numbers and actual earning potential. A well-crafted CIM not only highlights historical performance but also paints a clear picture of what the business can truly achieve.

FAQs

What are seller-specific EBITDA adjustments, and how do they affect business valuation?

Seller-specific EBITDA adjustments, often referred to as add-backs, are expenses or costs removed from a business’s financial records to showcase its true earning potential after ownership changes. These adjustments typically include non-recurring expenses (like lawsuit settlements or relocation costs), personal expenses (such as discretionary travel or entertainment), and instances where the owner’s compensation exceeds market norms. By stripping away these items, the adjusted EBITDA offers potential buyers a clearer view of the business’s cash flow.

In the lower-middle market, business valuations often hinge on an EBITDA multiple (e.g., 3–5× EBITDA). This means that increasing EBITDA through legitimate adjustments can have a significant impact on the implied purchase price. Properly documented add-backs not only improve the valuation but also give buyers greater confidence in the company’s financial health. For businesses looking to present these adjustments effectively, Deal Memo can help craft professional Confidential Information Memorandums (CIMs) that detail these changes, ensuring a clear and persuasive case for buyers.

What documents are needed to support EBITDA adjustments during due diligence?

To support EBITDA adjustments during due diligence, having clear and verifiable documentation is crucial. This not only validates the adjustments but also helps instill confidence in potential buyers. Here’s what you should have ready:

- A Confidential Information Memorandum (CIM) that outlines the business and provides a concise explanation for each adjustment.

- Historical financial statements – including income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements – covering the last 2–3 years, well-organized for easy review.

- Tax returns that match reported earnings and confirm that adjustments haven’t been included in filed taxes.

- Bank statements and expense records that clearly trace discretionary or one-time items, such as owner draws or unusual expenses.

- Owner compensation records, like payroll and benefits documentation, to justify any differences between actual pay and the adjusted market-rate figures.

- Contracts or invoices tied to one-off revenues or costs that are part of the adjustments.

These documents are key for a detailed quality-of-earnings (QOE) review, ensuring buyers can trust that the normalized EBITDA accurately represents the company’s financial health.

Why should you start preparing EBITDA adjustments well before selling your business?

Preparing EBITDA adjustments ahead of time gives you the opportunity to pinpoint, document, and justify non-recurring or owner-specific expenses that can be added back. Since buyers rely on Adjusted EBITDA to gauge sustainable cash flow, incomplete or rushed adjustments can damage your credibility and slow down negotiations.

By starting early, you’ll have time to organize supporting documentation, separate personal expenses, and standardize compensation. This results in a clear, well-supported figure that buyers can trust. Plus, every dollar added back gets multiplied by the buyer’s EBITDA multiple – often in the range of 5–7× – which can have a major impact on your final sale price. Early preparation also helps smooth out the deal process, minimizing surprises and keeping negotiations on track.

Deal Memo can simplify this process by providing custom Confidential Information Memorandums (CIMs) and Offering Memorandums (OMs) that highlight your EBITDA adjustments in a clear and professional way. With these materials ready in just 72 hours, you’ll be better equipped to present your business and maximize its value in the M&A process.