Senior debt is the cornerstone of financing in leveraged buyouts (LBOs), typically covering 30%-50% of the purchase price. Its secured, first-lien status ensures it’s repaid before other debt or equity, making it the least risky and most cost-efficient option for private equity firms. With interest rates generally between 4%-7%, it’s cheaper than junior debt or equity, helping maximize returns for investors.

Key points about senior debt in LBOs:

- Repayment Priority: Lenders are paid first in case of default or liquidation.

- Secured Loans: Backed by assets like real estate, equipment, or inventory.

- Lower Interest Rates: Floating rates tied to SOFR + 200-400 basis points.

- Loan Structure: Includes Term Loan A (TLA) with regular payments and Term Loan B (TLB) with a lump-sum repayment.

- Financial Covenants: Strict requirements like debt-to-EBITDA and interest coverage ratios ensure financial health.

While senior debt reduces financing costs and boosts equity returns, it comes with tight lender oversight and covenant obligations. Borrowers must carefully manage compliance to avoid default risks. This structured approach makes senior debt a key tool in balancing risk and reward in LBOs.

Types of Debt, Equity & Returns in the Capital Stack

What Is Senior Debt?

Senior debt represents the top-tier financing in a leveraged buyout’s capital structure. It holds the highest repayment priority, meaning lenders are paid before junior creditors, mezzanine lenders, or equity holders if the company faces financial trouble or liquidation.

What sets senior debt apart is its secured nature. Lenders typically have a first-lien claim on the borrower’s assets – these could include equipment, real estate, intellectual property, or even stock pledges. This means that in the event of default, lenders can seize these assets to recover their funds. This collateral significantly lowers the risk of losing capital compared to unsecured debt. That reduced risk also translates into more favorable borrowing rates for the company.

Because senior debt is the least risky type of financing in the capital stack, it usually comes with lower borrowing costs. While junior or mezzanine debt often carries annual rates of 10%–15%, senior debt typically falls between 4% and 7%. Most of these loans use a floating interest rate structure, combining a base rate like SOFR with an additional spread of 200 to 400 basis points. For example, with a SOFR of 3.5% and a 300-basis-point spread, the effective interest rate would be about 6.5%.

However, this lower cost comes with tighter oversight. Lenders enforce maintenance covenants, such as debt-to-EBITDA and interest coverage ratios, to keep tabs on the borrower’s financial health. Unlike the incurrence covenants tied to subordinate debt, these ongoing requirements help manage risk more effectively. Senior debt in LBOs typically matures within 5 to 8 years. Globally, the market for senior debt reached roughly $1.8 trillion as of June 2024, with over $700 billion traded in the U.S. alone in 2023. Its secured nature plays a central role in shaping these terms and conditions.

Priority Status and Secured Nature

The priority status of senior debt isn’t just a technical detail – it’s a legally binding claim that offers significant risk protection. In cases of bankruptcy or liquidation, senior secured lenders are first in line to recover their funds, backed by their first-lien interest in the borrower’s assets.

But this secured status comes with operational strings attached. Senior lenders often maintain the right to monitor the borrower’s activities and may impose restrictions on asset sales, additional borrowing, or major business changes. As Umbrex explains:

Senior debt holders generally have a lien on the borrower’s assets, granting them the right to seize and liquidate collateral before other debt classes (such as second lien or mezzanine).

This system ensures lenders maintain control over their collateral throughout the loan’s duration.

Interest Rates and Loan Terms

Senior debt’s lower risk profile directly influences its financing terms. Most senior loans in LBOs come with floating interest rates. These rates typically combine a base rate – historically LIBOR but now mostly SOFR – with a fixed spread that adjusts based on market conditions. The spread, usually between 200 and 400 basis points, reflects factors like the borrower’s creditworthiness, industry-specific risks, and broader market trends. With SOFR rates generally between 3% and 5%, total borrowing costs for senior debt usually range from 4% to 7%.

Loan maturities are designed to match the investment’s timeline. Term Loan A (TLA) facilities, often held by commercial banks, usually span 5 to 7 years and require regular principal payments. Term Loan B (TLB) facilities, on the other hand, are typically held by institutional investors like CLOs and mutual funds. These loans have maturities of 5 to 8 years and feature minimal amortization, with a lump-sum payment due at the end.

Additional costs may also apply. For instance, revolving credit facilities often charge an undrawn commitment fee of 0.25% to 0.50% annually on unused credit lines. Upfront fees from arrangers can range from 1% to 5% of the loan amount. Some loans are issued at an original issue discount, meaning the borrower receives less than the loan’s face value but repays the full amount, generating extra yield for the lender.

Unlike high-yield bonds, senior bank debt typically doesn’t include prepayment penalties. This flexibility allows borrowers to refinance or pay off loans early if cash flow improves, offering a strategic advantage over fixed-rate instruments. For example, Dunkin’ Brands used its strong cash flow to manage senior debt following a management buyout, eventually paving the way for its public offering.

How Senior Debt Fits in the LBO Capital Stack

Senior debt plays a crucial role in the financing structure of a leveraged buyout (LBO), sitting at the top of the capital stack. This position ensures that senior debt is repaid first in the event of financial distress, giving senior lenders first-lien claims on the company’s assets – everything from equipment and real estate to intellectual property.

In a standard LBO, senior debt typically makes up about 30% to 50% of the total capital structure. Private equity sponsors, on the other hand, usually contribute 20% to 40% of the purchase price as equity, with the rest financed through other debt instruments. This layered structure allows sponsors to balance borrowing costs while still aiming for high returns.

Each layer of the capital stack comes with its own risk and cost profile. Senior debt generally has the lowest interest rates – ranging from 4% to 7% – due to its secured nature. In contrast, junior debt and mezzanine financing often carry higher rates, typically between 10% and 15%. Senior debt itself is further divided into two key components: revolver loans and term loans.

Revolver Loans and Term Loans

Senior debt is commonly split into revolving credit facilities and term loans, each serving a distinct purpose.

A revolving credit facility, or revolver, functions much like a corporate credit card. It provides short-term liquidity to cover working capital needs. Companies can borrow as needed and repay without penalties. Lenders charge interest on the drawn amount, typically at SOFR plus 200 to 400 basis points, and also apply an undrawn commitment fee on unused credit.

Term loans, in contrast, are used primarily to finance the acquisition itself. These loans come in two main types:

- Term Loan A (TLA): Issued by commercial banks, TLAs have maturities of 5 to 7 years and require regular principal repayments.

- Term Loan B (TLB): Provided by institutional investors, TLBs generally mature in 5 to 8 years. They involve minimal amortization, with most of the principal repaid in a single "bullet" payment at maturity.

| Feature | Term Loan A (TLA) | Term Loan B (TLB) |

|---|---|---|

| Lender Type | Commercial Banks | Institutional Investors |

| Amortization | Regular repayments | Minimal, with a balloon payment at maturity |

| Maturity | 5–7 years | 5–8 years |

| Interest Rates | Lower rates | Higher rates |

Leverage and Coverage Ratios

Financial metrics are critical in determining how much senior debt can be included in an LBO. One key measure is the Debt-to-EBITDA ratio, which evaluates total debt capacity. In mid-market and larger deals, overall leverage typically ranges from 4.0x to 6.0x EBITDA. However, senior debt is often capped at around 3.0x EBITDA to maintain a safety margin.

Coverage ratios are equally important, as they ensure the company generates enough cash flow to meet its debt obligations. Lenders usually require an Interest Coverage Ratio (EBITDA divided by interest expense) of at least 2.0x. For companies with high capital expenditure needs, a stricter measure – (EBITDA minus CapEx) divided by interest – is often required to exceed 1.6x.

| Metric | Typical LBO Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Total Debt / EBITDA | 4.5x – 5.5x | Assesses overall leverage capacity |

| Senior Debt / EBITDA | ~3.0x | Limits the senior debt portion |

| EBITDA / Interest Coverage | >2.0x | Ensures ability to cover interest payments |

| (EBITDA − CapEx) / Interest | >1.6x | Confirms coverage after reinvestment |

Senior lenders enforce these metrics through maintenance covenants, which are reviewed regularly – usually on a quarterly basis. If a company’s ratios fall below agreed thresholds, lenders may impose restrictions on additional borrowing, limit asset sales, or even demand immediate corrective actions.

Benefits of Using Senior Debt in LBOs

Senior debt plays a pivotal role in leveraged buyouts (LBOs), offering financial advantages that can significantly impact deal performance. With its secured nature and priority status, senior debt not only safeguards lenders but also provides a cost-efficient way to structure financing and boost equity returns.

Lower Cost of Capital

Senior debt, secured by a first-lien claim, typically comes with interest rates ranging from 4% to 7%, which is far more affordable compared to mezzanine financing rates of 10% to 15% – or even 18% to 25% when equity warrants are included. By prioritizing senior debt over more expensive mezzanine or equity financing, deal sponsors can reduce the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). This, in turn, frees up cash flow that can be reinvested in the business or used to pay down debt faster.

"Senior Debt is the ‘cheapest’ of all of the financing instruments used to buy a company via LBO: it has a lower cost of capital than other tranches of the capital structure, as it is the first in line… to receive value during a liquidation."

A great example of this was the February 2013 acquisition of H.J. Heinz Company by Berkshire Hathaway and 3G Capital for approximately $28 billion. The deal relied heavily on senior secured debt, backed by Heinz’s assets, which ensured repayment priority and kept financing costs lower. This strategic use of senior debt helped set the foundation for long-term financial success while minimizing capital costs.

Increased Equity Returns

The affordability of senior debt also amplifies equity returns. In many LBOs, senior debt can cover 50% to 80% of the purchase price, leaving sponsors to contribute only 20% to 35% of the capital themselves. As the company generates cash flow and gradually pays down its senior debt, equity value grows disproportionately. Since equity sits at the bottom of the capital structure, any increase in enterprise value or reduction in outstanding debt translates into significant gains for equity holders. This structure allows private equity investors to aim for annual internal rates of return (IRRs) in the range of 20% to 40%.

Take the 2006 management buyout of Dunkin’ Brands as an example. A consortium of private equity firms used senior debt to finance the transaction. Over time, the company expanded significantly and eventually went public in 2011. This case highlights how senior debt not only keeps financing costs manageable but also provides a pathway to substantial equity growth and long-term success.

Risks and Covenant Requirements

Senior debt offers advantages, but it comes with strict oversight that can limit a company’s strategic choices. These restrictions, known as covenants, are designed to safeguard lenders’ interests within the larger leveraged buyout (LBO) financing structure. Building on the secured and priority aspects of senior debt, lenders enforce financial covenants – binding rules that borrowers must follow. If these covenants are breached, it triggers a technical default, which can lead to demands for immediate repayment or penalty interest rates.

Financial Covenants and Restrictions

Senior debt agreements typically include three categories of covenants that influence how borrowers operate.

- Affirmative covenants: These require borrowers to take specific actions, like submitting regular financial reports or maintaining adequate insurance coverage.

- Negative covenants: These restrict certain activities, such as selling assets, pursuing mergers or acquisitions, or issuing dividends without lender approval.

- Financial covenants: These set measurable thresholds, such as limiting the Leverage Ratio (total debt to EBITDA) to 2.0x–3.0x in the middle market or requiring an Interest Coverage Ratio where EBITDA must be at least twice the interest expense.

One of the most thorough tests is the Fixed Charge Coverage Ratio, which compares EBITDA to the sum of interest, principal payments, capital expenditures, lease payments, and management fees. These tests are often conducted quarterly as maintenance checks. However, the rise of covenant-lite loans has shifted many agreements to incurrence tests, which are only triggered by specific actions, like issuing new debt.

Borrowers should negotiate covenants with enough flexibility – or "headroom" – to handle minor setbacks without breaching the terms. Including cure provisions in loan agreements is also essential. These provisions allow a grace period to address violations before lenders can take punitive measures. Such safeguards serve as early warning systems, signaling financial trouble before it escalates.

Default Risks and Remedies

When a covenant is breached, lenders gain additional rights. They may demand immediate repayment of the loan, increase interest rates, or exercise their security interest to seize and sell collateral. In severe cases, lenders might step in to influence management decisions or block strategic moves, such as acquisitions or dividend distributions. A well-known example is the 1989 acquisition of RJR Nabisco by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. (KKR). The $25 billion deal, financed with $19 billion in debt secured by the company’s assets, eventually led to financial restructuring due to the overwhelming debt burden.

Addressing covenant breaches can be both expensive and time-consuming, often involving legal negotiations and waiver fees paid to lenders. To mitigate these risks, CFOs should implement real-time monitoring tools to track covenant compliance and evaluate how planned business activities might impact future adherence to these terms.

sbb-itb-798d089

Repayment Mechanisms and Cash Flow Sweeps

Senior debt in leveraged buyouts comes with structured repayment plans that vary across different types of loans. Term Loan A (TLA) is set up for full, even amortization over a 5- to 7-year period. Borrowers make significant annual principal repayments throughout the loan’s term, which steadily reduces the debt burden but requires consistent cash flow generation. On the other hand, Term Loan B (TLB) has minimal annual amortization – usually just 1% per year – with a large "bullet" payment due at maturity, typically in 5 to 8 years. This setup allows the borrower to conserve cash during the investment period but creates a concentrated repayment challenge at the end of the loan term.

Cash flow sweeps offer an additional mechanism to accelerate debt repayment. These require borrowers to use a portion of their excess free cash flow to reduce the senior debt principal. The revolving credit facility plays a key role here, functioning much like a credit card. Borrowers can draw funds as needed and repay them immediately when extra cash becomes available, without incurring prepayment penalties.

"A company will ‘draw down’ the revolver up to the credit limit when it needs cash, and repays the revolver when excess cash is available (there is no repayment penalty)." – Keith Yagnik, Lions Financial

These repayment structures help reduce both the debt and interest burden, which ultimately enhances the sponsor’s internal rate of return (IRR). However, lenders enforce strict financial maintenance covenants, such as quarterly-tested debt coverage ratios, to ensure the company generates enough cash to meet its obligations. While senior debt typically has a legal maturity of 5 to 8 years, lenders often expect full repayment within 3 to 5 years, aligning with the private equity firm’s planned exit timeline.

How Senior Debt Works with Junior Debt and Equity

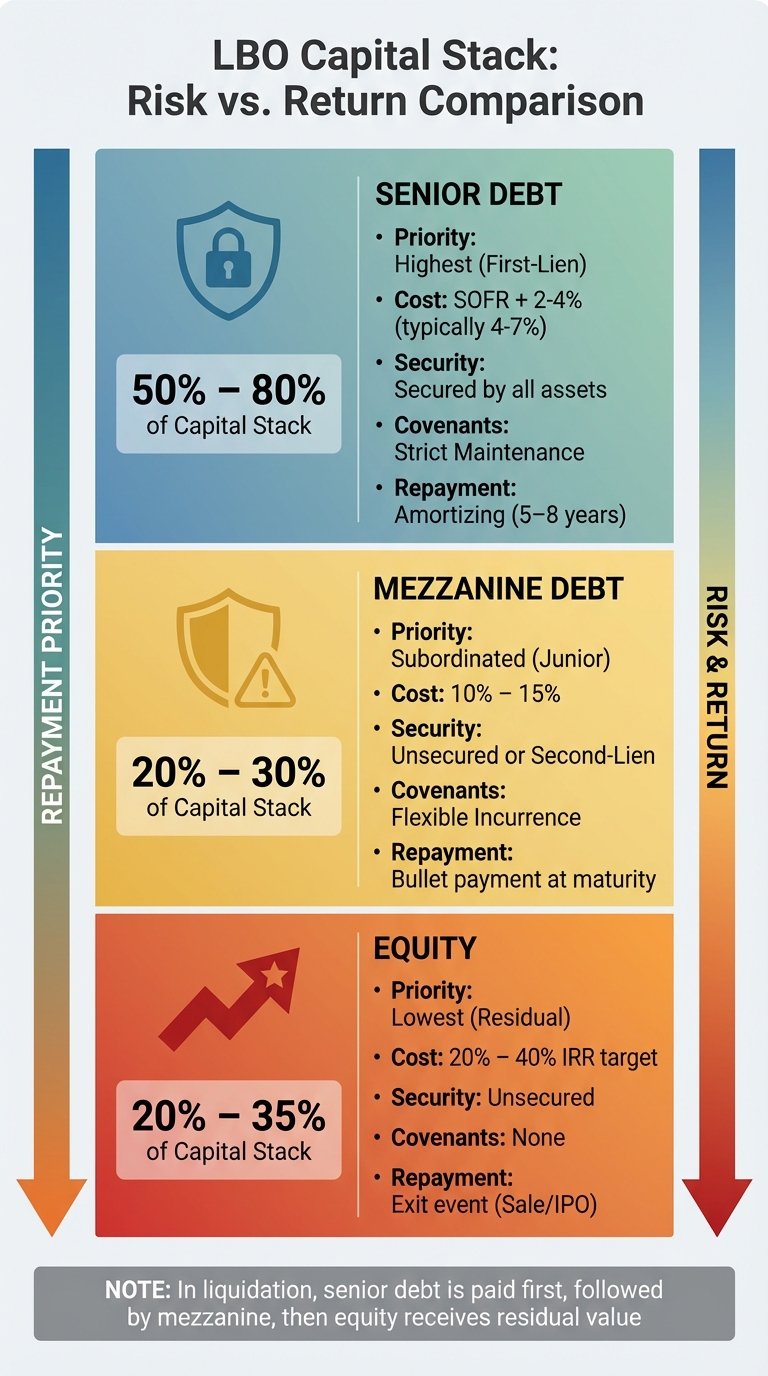

LBO Capital Stack Structure: Senior Debt vs Mezzanine vs Equity Comparison

Senior debt is the backbone of the LBO capital stack, typically making up 50% to 80% of the total financing. It stands out for its lower cost of capital, which lenders accept in exchange for its secured status and reduced risk. Positioned at the top of the repayment hierarchy, senior debt gives lenders the highest level of repayment priority, making it an attractive option for both borrowers and lenders.

Complementing senior debt, mezzanine financing fills the gap between senior debt and equity. This layer usually accounts for 20% to 30% of the capital stack and comes with higher interest rates – often ranging from 10% to 15% – to reflect its subordinated position. Mezzanine lenders often include equity kickers, such as warrants, to gain a share in the company’s potential growth, aiming for total returns in the high teens to low twenties. Unlike the rigid maintenance covenants tied to senior debt, mezzanine financing typically uses more flexible incurrence covenants, which are triggered only by specific borrower actions, like raising additional debt.

At the base of the capital stack lies equity, which acts as the "first loss" layer. Equity holders absorb any initial losses before debt holders are affected, making it the riskiest part of the capital structure. Private equity sponsors generally contribute 20% to 35% of the purchase price in equity. Despite its high risk, equity offers the greatest potential reward, as it captures all remaining value after debt obligations are satisfied. Private equity sponsors often aim for annual internal rates of return between 20% and 40%.

The relationship between these financing layers is governed by intercreditor agreements, which define the rights of each creditor class. These agreements establish the repayment order – senior debt first, followed by junior debt, and finally equity – and outline default remedies. Senior lenders maintain significant control through strict financial covenants, which may limit dividend payments or additional borrowing until senior obligations are fully met. This structure ensures a clear repayment hierarchy, protecting the interests of each layer.

Here’s a breakdown of key distinctions between senior debt, mezzanine debt, and equity:

| Feature | Senior Debt | Mezzanine Debt | Equity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Priority | Highest (First-Lien) | Subordinated (Junior) | Lowest (Residual) |

| % of Capital Stack | 50% – 80% | 20% – 30% | 20% – 35% |

| Cost | SOFR + 2-4% | 10% – 15% | 20% – 40% IRR |

| Security | Secured by all assets | Unsecured or Second-Lien | Unsecured |

| Covenants | Strict Maintenance | Flexible Incurrence | None |

| Repayment | Amortizing (5–8 years) | Bullet payment at maturity | Exit event (Sale/IPO) |

Documentation for Senior Debt Financing

When it comes to senior debt structures, having well-prepared documentation is crucial for securing financing and managing risks effectively.

In a leveraged buyout (LBO), securing senior debt hinges on clear, detailed documentation that outlines the transaction’s structure, associated risks, and repayment capacity. Two key documents in this process are the Confidential Information Memorandum (CIM) and the Offering Memorandum (OM). The CIM provides an in-depth operational and financial overview, serving as a marketing tool during the syndication process. This is when a lead arranger assembles a group of lenders to collectively fund portions of the senior debt. The OM, on the other hand, is a formal legal document used in private debt placements, presenting the debt instrument to pre-selected investors in private markets or the bond market.

A critical component of these documents is the "sources and uses of funds" table. This table breaks down where the capital comes from – whether through equity, senior debt, or junior debt – and how it will be allocated, such as for the purchase price, refinancing, or fees. Additionally, the documentation must include important financial metrics, like leverage and coverage ratios. For example, lenders often expect a Debt-to-EBITDA ratio between 4.0× and 6.0× and an Interest Coverage Ratio of at least 2.0×. The collateral and security package should also be clearly outlined, specifying a first-priority lien on assets such as physical property, intellectual property, receivables, and inventory. These details help establish robust risk controls and repayment mechanisms.

For firms looking to streamline the preparation of these documents, services like Deal Memo offer customizable, white-labeled CIM and OM packages with rapid 72-hour turnaround times and unlimited revisions to ensure alignment with current market standards. As Akin aptly puts it:

Successful leveraged finance transactions require not just sophisticated technical skill, but also deep knowledge of ‘what’s market’ – both commercially and in negotiating critical documentation.

High-quality documentation plays a pivotal role in expediting the syndication process and securing favorable terms. By creating professional, well-organized materials, the lead arranger can confidently present the debt offering, attracting investors and facilitating smooth syndication.

Given the tight timelines often associated with LBO financing, outsourcing the preparation of CIMs and OMs allows investment banking teams to focus on structuring the deal itself. Comprehensive documentation that addresses intricate details – such as covenant-lite structures, most favored nation pricing, and intercreditor agreements – ensures both legal and financial considerations are managed effectively during the proposal and commitment phases. This approach fosters agility and smooth transaction execution, which are essential for meeting the demanding deadlines of today’s competitive market.

Conclusion

Senior debt serves as the backbone of LBO financing, typically accounting for 30%–50% of the total capital structure. Its secured, first-lien status ensures it comes with the lowest cost of funds, making it a key driver for private equity sponsors aiming to reduce upfront equity contributions while boosting potential returns. This unique positioning makes senior debt an essential element in structuring successful LBO transactions.

However, the benefits of senior debt come with the need for careful planning. High leverage can amplify returns, but it also increases the risk of default. To manage this, lenders enforce strict financial covenants. If these covenants are breached, it can trigger a technical default, potentially wiping out equity returns for sponsors. This underscores the importance of disciplined structuring to balance risk and reward.

Sponsors must also navigate the nuances of senior debt tranches. For instance, Term Loan A typically involves steady amortization over 5–7 years, while Term Loan B features minimal amortization and a large bullet payment at maturity. These differences allow sponsors to tailor capital structures to match cash flow needs and growth plans effectively.

Another critical factor in securing favorable senior debt terms is high-quality documentation. Detailed and well-prepared Confidential Information Memorandums (CIMs) and Offering Memorandums (OMs) are instrumental in building lender confidence. These documents should clearly outline the sources and uses of funds, collateral arrangements, and financial projections. For teams working under tight deadlines, services like those offered by Deal Memo, which deliver white-labeled CIMs and OMs within 72 hours, can streamline the syndication process and reinforce lender trust.

FAQs

What are the key risks of using senior debt in a leveraged buyout (LBO)?

Using senior debt in a leveraged buyout (LBO) comes with a set of challenges that both investors and businesses need to weigh carefully. One major issue is credit risk, as the company must consistently generate enough cash flow to cover its debt payments. High levels of leverage can also strain cash flow, making it harder to juggle everyday operating costs and debt repayment schedules.

On top of that, senior debt typically includes strict covenants that can restrict the company’s financial and operational decisions. Borrowers are also exposed to market risks, such as rising interest rates, which could drive up the cost of borrowing. Another concern is liquidity risk, which surfaces if the company has trouble securing additional funds or refinancing its debt when necessary. For these reasons, it’s crucial to evaluate the company’s financial stability and overall health before committing to senior debt in an LBO.

What are the key differences between senior debt and mezzanine financing in terms of cost and structure?

Senior debt holds the top spot in a company’s capital structure, secured by a first-lien claim on its assets. Because it comes with lower risk, it generally offers lower interest rates and includes stricter financial covenants. This makes senior debt a more cost-efficient funding option, though it leaves the borrower with less flexibility.

On the other hand, mezzanine financing sits below senior debt but above equity in the capital stack, carrying higher risk for lenders. To balance that risk, it typically features higher interest rates and may include perks like equity kickers or conversion rights. These features give lenders the opportunity to secure ownership stakes if the borrower defaults. While both senior debt and mezzanine financing are common in leveraged buyouts (LBOs), their roles differ: senior debt prioritizes asset-backed security and covenant enforcement, while mezzanine financing offers lenders the chance for higher returns in exchange for taking on more risk.

How do financial covenants help manage senior debt in leveraged buyouts?

Financial covenants are an essential part of loan agreements, designed to help senior lenders keep a close eye on risk and financial health. These provisions require borrowers to meet specific financial benchmarks, like maintaining a minimum debt-service coverage ratio or adhering to a maximum leverage ratio. The goal? To ensure the borrower stays financially sound and capable of repaying its senior debt.

In the context of leveraged buyouts (LBOs), senior debt typically comes with the strictest covenants. Why? Because it has the highest repayment priority and the lowest cost of capital. These covenants often restrict activities such as taking on more debt, issuing dividends, or selling significant assets. Additionally, they mandate regular reporting of financial metrics, which acts as an early-warning system for lenders. This setup not only promotes financial discipline but also helps catch potential issues early, reducing the risk of default throughout the transaction.